Why SuperEarths are the goal

From the avalanche of recent discoveries (over 3500 confirmed and counting), we have learned something rather unexpected. Despite our strong observational bias for detecting large, gaseous giants (i.e. Saturn and Jupiter type planets), current Kepler and radial velocity and microlensing statistics show a very different picture. Contrary to expectations, super-Earths (planets roughly between 1 - 10 Earth masses) are in fact the most abundant planets, especially around late-type stars. In other words, our galaxy is one of Earths and slightly larger planets, not giants. This discovery poses a rather fundamental question: “What exactly are super-Earths?”, “How do they form?”, “Are they habitable and what is the weather like?” - To which the current response is a somewhat sobering: “We don’t really know”. Though most common in the galaxy they are entirely absent (unless planet 9 is confirmed) from our own solar system. Super-Earths encompass an astonishing range of worlds. Unlike hot-Jupiters (the best understood class of exoplanets), where most variations can to first order be attributed to initial elemental abundances, super-Earths are orders of magnitudes more complex.

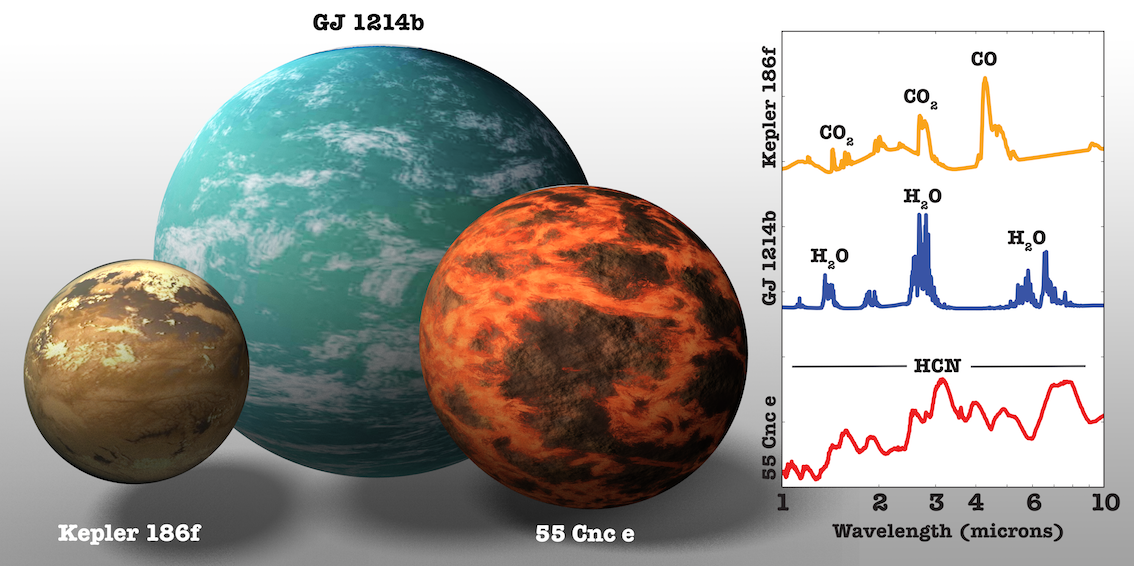

The figure above shows three very different worlds, ranging from giant Mars and Venus type planets to large ocean worlds and molten lava planets. To date, we can only speculate how diverse this class of planets is as we only have a limited understanding of their bulk chemistry, formation histories or climate.

Basic information about their densities seems to suggest that there is a variety of possible bulk compositions. Though this can be deceptive. For instance, although a 100% water composition fits some of the mass-radius data, based on formation constraints, the presence of heavier refractory materials on these planets is expected. By corollary, one then requires additional, lighter components – i.e. H/He – to achieve the mean density of a 100% water composition. As in-situ measurements remain out of question for some time, with the closest exoplanet Proxima Centauri b (itself a super-Earth) being 4.24 light years away, we rely on remote sensing techniques.

Here, transit spectroscopy comes to the rescue.

When these planets pass in-front of their host star, some of the stellar light traverses through the thin atmospheric annulus of the planet. By measuring the signatures of molecular tracers (e.g. H2O, CH4, CO, CO2) at different wavelengths, we can constrain the bulk chemistry of the atmosphere. The top figure shows simulated transmission spectra for three very different worlds. Their atmospheric trace gases allow us to gain a robust insight into the composition of the upper atmosphere of super-Earths. Amongst others, this will determine the extent of compositional segregation between the atmosphere and the interior. Hence, removing the degeneracy originating from the uncertainty in the presence and mass of H/He atmospheres.

In other words, by measuring the light that passes through these thin atmospheres, we can identify the chemistry of these planets, the possible bulk composition and formation histories, if they are cloudy and even whether some of them may be able to harbour life. By measuring many of these SuperEarths, we will hopefully be able to answer some of these fundamental questions above and really put our solar system into the broader context of the galaxy.