Deep learning Saturn

Today we’ve published a paper on deep learning applied to Saturn in Nature Astronomy. The link to the paper is here. We’ve also got a press release here.

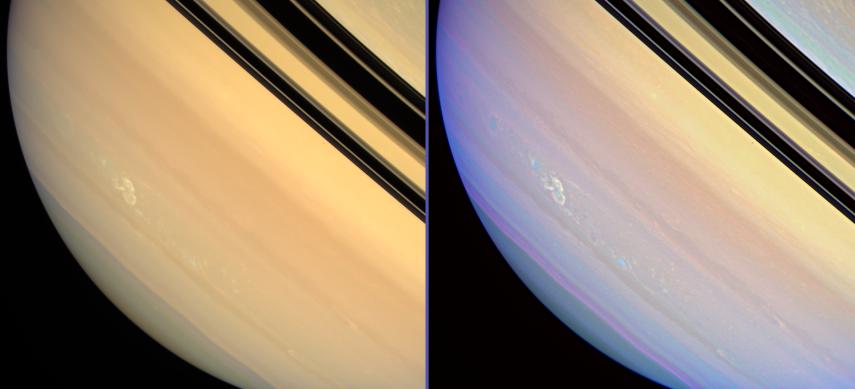

In this paper, we used neural networks to map the storms of Saturn’s southern hemisphere. What we found was unexpected, large upwellings of ammonia, dragged up by the storms from the deep atmosphere of the planet.

It is probably fair to say that the Cassini-Huygens mission to Saturn and its moons was one of the most successful scientific missions ever conducted. Launched back in 1997, it was actively circling the Saturnian system for over 13 years. The quality and amount of data gathered truly revolutionised our understanding of Saturn and the outer planets. In September 2017, Cassini famously plunged itself into Saturn to avoid contaminating any of its moons in the future. Cassini is gone but the enormous data archive still holds many surprises. To me the biggest surprise was how very little had actually been fully analysed and remains in the archives. I’m not a planetary scientist by training, well I characterise exoplanets but that’s somewhat different, and I was astonished to find out that not only Saturn had huge archives ripe for re-analysis but most other planets (Venus, Mars, Jupiter etc) do too.

In exoplanets we specialise in building machine and deep learning approaches to data analysis, so we are quite used to dealing with large data sets. Here we had some of the largest data sets available to astronomy and we were keen to do something about that. When Caitlin Griffith, my US colleague, and I started the project, we thought we’ll take it easy and re-analyse an already published data set on a weird bright cloud around a southern hemisphere storm. Baines et al. 2009 attributed this feature to ammonia ice before, which (unlike on Jupiter) is quite rare to see on Saturn. I wrote the neural net in a fortnight based on Earth observation literature I was reading at the time and ran the data set through. Within 10 minutes we had the result. To understand what the result actually means and to verify that it is actually real, took us a year. It turned out that the original ammonia detection of 2009 only really saw the proverbial tip of the iceberg and in fact there seemed to be a huge upwelling of ammonia from the deeper parts of Saturn around the dark storm. Not only was the feature bigger than initially expected but smaller storms seemed to also have smaller upwellings, which intuitively makes sense but was not observed before.

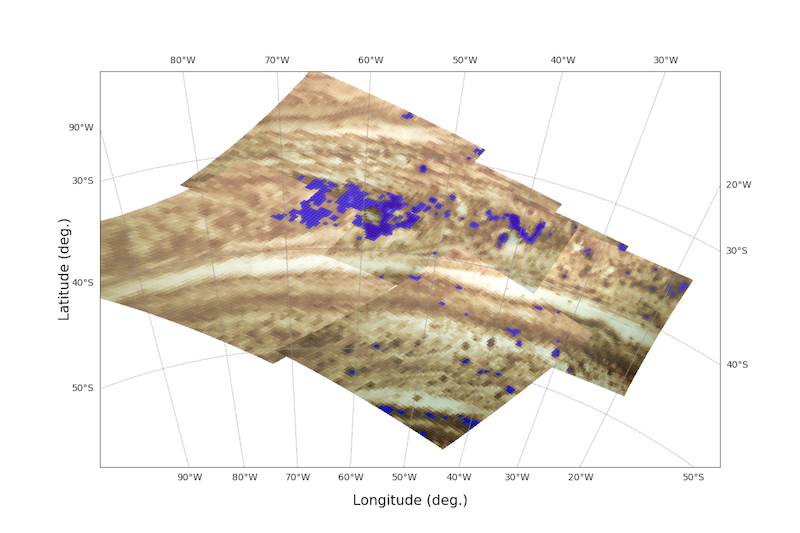

The image above shows the extend of the ammonia clouds. They roughly compare in size to 70% of the Earth’s surface.

The image above shows the extend of the ammonia clouds. They roughly compare in size to 70% of the Earth’s surface.

The most surprising of these findings though was that analysing planetary hyperspectral image data is really not that hard and once you trained your deep learning or clustering algorithm on a feature set, you can analyse large portions of the surface quickly. Having a global view of the planet’s composition or cloud features will be very valuable in understanding the dynamics of the gas giants, and the geology of the rocky planets.

We’re now taking PlanetNet to Mars and Venus. Let’s see what we will find!