Direct Imaging with deep learning

Discovering planets is a difficult task, and it is especially true for direct Imaging. In this blog post, I am going to briefly explain how neural network can be used to detect planets.

Wait… What is Direct Imaging?

Direct Imaging is one of the commonly used techniques to discover the existence of far away planets. In principle, a telescope is tasked to look at a specific stellar system and literally, ‘took a picture’ of the system. However, as you can imagine, the light from the parent star will be so much brighter than the planet (think about how our Sun lights up the sky even though it is 149 million km away ) and thus astronomers will usually put a mask at the star in order to substantially lower the brightness of the star.

Why is it so difficult?

Masking the contribution from the star does not resolve the issue, our target is still far too faint compared to the leftover lights from the star.

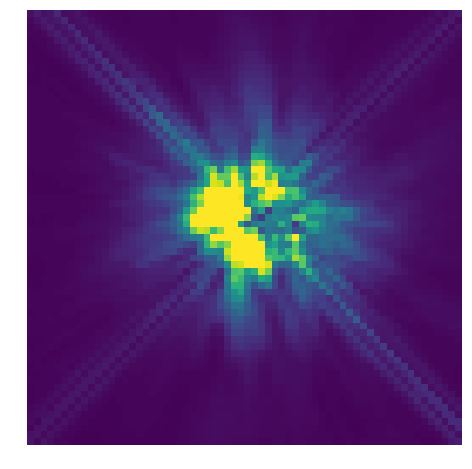

These leftovers (shown above ) lights formed a specific pattern, which we called the PSF (point spread function) through the scattering process. This pattern, however, is quasi-static, meaning that they are not-so-static (but not as dynamic neither) in time. The pattern itself is dictated by the optical path between the star, coronagraph and the detector, which is static as long as they are intact. However, during the operation the telescope itself will undergo very slight deformation due to tracking and thermal properties of the material, making the shape of the pattern to slowly vary with time. This phenomenon is difficult to model, and any residual light can easily overwhelm the light coming from the planet itself, rendering it a big problem in the field of direct Imaging. So far, there are only around 100 planets and sub-stellar companions discovered through direct Imaging. A tiny figure compared to 3000 known planets.

An alternative approach — Neural Network.

While many efforts in the community have focused on suppressing the speckle pattern to reveal the presence of the planet, we figured that if the end goal is to find planets, why don’t we bypass the speckle pattern and detect their presence? To do that, we utilised a specific deep learning architecture called Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). This kind of network extracts different features from an image (for instance, eyebrows, mouth and skin colour from our face), and learnt the spatial relationships with one another. In this paper, CNN is used to classify whether a given image contains a planet (positive class) or not (negative class). In the process, we have also utilised GAN, another type of deep learning architecture capable of reproducing images, to enrich the size of the training set and balance the number of examples from both classes.

Detecting is good, locating is better.

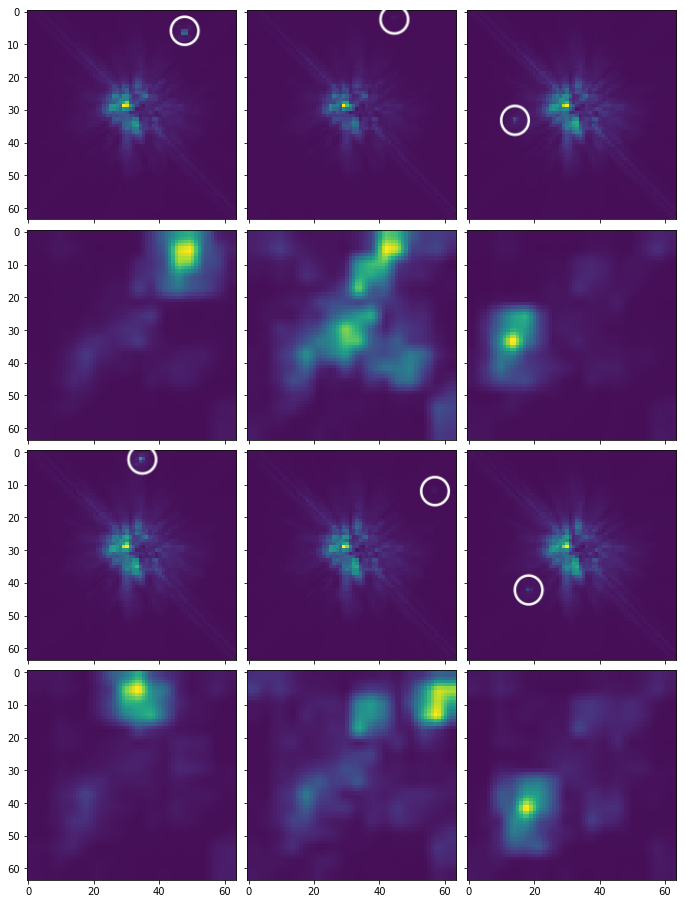

Our CNN is trained to classify whether a given image has a planet or not. However, how does it come to a decision? What prompts it to say there is a planet? To address these questions (and for our own peace of mind), we used Grad-CAM to visualise the decision-making process of our CNN. This technique constructs the corresponding class activation maps for each image and highlights the region that contributes most to its decision, in our case, the location of the planet. Figure below shows the results of our CNN when applied to some real data. The bright spots here are background stellar light rather than planets.

This is a rough summary of what we did for this project. If you are interested to understand what we did, every tiny little detail of our project can be found here. If you want to have a go for yourself, please feel free to download the code from our Github and the sorted data from here.

What’s Next?

We are going to apply our network to known planetary systems! Stay tuned!